From the background of a translation: The first edition in French of „The History of the Othoman Empire” by Dimitrie Cantemir and its political implications

Text: Andreea Ștefan / photo: Marius Amarie

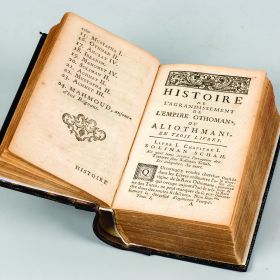

Demetrius Cantemir, Histoire de l’Empire Othoman où se voyent les causes de son agrandissement et de sa décadence avec des notes très instructives, translated into French by M. de Joncquières, Commandeur, Chanoine Régulier de l’Ordre Hospitalier du Saint Esprit de Montpellier, Paris, 1743.

Material: Embossed paper

Sizes: 25.5 x 19.4 cm

Dating: MDCCXLIII [1743]

Description: 2 volumes bound in one book: [8]-xlviii-300 p. ; [4]-389-[1] p.; format 4°

Dimitrie Cantemir’s work (1673-1723) is the first and foremost example of acknowledging the writings of a Romanian scholar at the European level. The linguistic vehicle of Cantemir’s best-known works was, obviously, an international language in most of the cases, usually Latin. This considerably facilitated the circulation of his books, many of which approached current topics that used to be ignored by his contemporary researchers. The best example in this respect is Incrementorum et decrementorum Aulae Othmannicae (The History of the growth and decay of the Othman Empire), a fundamental work that had been referential for European Turkology up to the publication of the monumental work Geschichte des osmanischen Reiches (The History of the Othman Empire), published in 10 volumes (1827-1835) by the Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856) in Pest.

The translation that replaced the original

Though written in Latin, the language of scientific circulation, which made it immediately accessible to the erudite public, The History of the Othman Empire was known, for centuries, due to a translation. It is about the volume translated by N. Tindal and published in London, at the J., J. and P. Knapton publishing house, in 1734. The Latin manuscript that was the source-text for this translation was in the possession of Dimitrie Cantemir’s son, Prince Antioh Dimitrievici Cantemir (1708-1744), the ambassador of the Russian Empire in London. He lost his possession over the precious manuscript during his stay in London, when he left it as a guarantee for unpaid debts. After this moment, the manuscript had been considered lost up to 1984, when the Romanian scholar Virgil Cândea discovered it in the collection of Houghton Library (Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts). Actually, Tindal’s English translation had remained, up to the end of the 20th century, the reference that was later used for the editions in French and German.

In March 1738, Antioh Cantemir was appointed the Russian ambassador in Paris and, during the following years, he took care of publishing his father’s book in the French capital. This mission was taken by Commodore M. de Joncquières, a cleric in the Order of the Hospitallers of the Holy Spirit, who used the English edition for his translation. Nevertheless, the book is also a political gesture and the translator noticed this. Consequently, he aptly dedicated the work to Philippe, Count of Noailles (1747-1794), and his choice was not fortuitous. The family of de Noailles was closely related to the Sublime Porte through historical ties. François de Noailles, bishop of Dax, was the ambassador of Charles IX in Istanbul (1571-1575) during the critical period after the Battle of Lepanto (1571), and his successor to that position was his younger brother Gilles de Noailles.

A history written and circulated next to Power

The history written by Dimitrie Cantemir is the result of both documentation and direct observation. His presence in Istanbul as a guarantee for the loyalty of his father, the ruler of Moldavia, in front of the Sublime Porte is an extremely important biographical detail in the case of the scholar-prince. At the end of the 17th century, in the entire Balkan and Eastern space, Istanbul offered the best conditions for studying the classical culture or for getting into contact with Occidental ideas. The Patriarchal Academy in Constantinople, reformed according to the principles of the neo-Aristotelian philosopher, Theophilos Corydalleus (1563–1646), offered a solid classical education. Cantemir, author of ample treatises in Ancient Greek and Latin, testifies for the level at which classical languages were learned at the time in the Empire’s Hellenophone environment.

On the other hand, through the Western Powers’ embassies in Istanbul, the Orient received echoes of the contemporary academic debates in the great European capitals. In The Hieroglyphic History Dimitrie Cantemir himself evokes the cosmopolitan environment and the cultural effervescence of the metropolis on the shores of the Bosporus. Moreover, this is the very place where he could learn Turkish and got familiar with the complex hierarchical Ottoman culture. His History is the result of this fortunate ensemble of circumstances. Placed in the center of the Empire’s administration, having access to the dignitaries and the archives, benefitting from freedom within the area of the Capital, Dimitrie Cantemir had the best sources of information for writing his History.

The work was finished around 1717 in Russia, where the prince retired, together with his family, after the defeat of his great ally, Peter the Great, on the Prut River (1711). Under the Tsar’s protection, Cantemir focused on humanities, and his sons, whose education was carefully supervised by their father, made his work known to the Occident.

We have already discussed the decisive part that Antioh Cantemir’s embassies in London and then in Paris played in the translation and circulation of the History of the Othman Empire. The translation into French of Antioh’s own poetic writings is also related to his stay in Paris. The volume was posthumously published in Paris in 1750. It has a double significance, as the original in Russian marks the beginnings of poetry in this language.

Going back to the History of the Othman Empire, it is worth mentioning that 1745, when the German edition was published in Pest, marks the last step in paving its way to European recognition. Once translated into German as well, the book imposed itself, for almost a century, as the most accessible and the most documented scientific work dedicated to the Ottoman Empire.

Editions

1734: The History of the growth and decay of the Othman Empire, originally written in Latin by Demetrius Cantemir, translated into English by N. Tindal, London, J., J. and P. Knapton

1743: Histoire de l’Empire Othoman où se voyent les causes de son agrandissement et de sa décadence avec des notes très instructives, translated into French by M. de Joncquières, commodore and cleric in the Order of the Hospitallers of the Holy Spirit in Montpellier, Paris

1745: Geschichte des osmanischen Reichs nach seinem Anwachse und Abnehmen, aus dem Englischen übersetzet [The History of the growth and decay of the Othman Empire, translated from English], Hamburg, Christian Herold

1999: The growth and decay of the Othman Empire: the original text in Latin in the final form reviewed by the author, a facsimile of the manuscript Lat-124 from Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., published with an introduction by Virgil Cândea, Bucharest, Roza Vânturilor

2002: Demetrii principis Cantemirii Incrementorvm et decrementorvm avlae othman(n)icae sive aliothman(n)icae historiae a prima gentis origine ad nostra vsqve tempora dedvctae libri tres, praefatus est Virgil Cândea, critice edidit Dan Sluşanschi, Timişoara, Amarcord Publishing House

2010: Incrementorum et decrementorum Aulae Othmannicae: novel manuscript in facsimile, preface by Virgil Cândea, edition coordinated by Constantin Barbu, Craiova, Revers Publishing House, 2 vol.

2015: The growth and decay of the Othman Empire, the edition of the text in Latin and the critical apparatus by Octavian Gordon, Florentina Nicolae and Monica Vasileanu, translated from Latin by Ioana Costa, with a foreword by Eugen Simion and an introductory study by Ştefan Lemny, Bucharest, The National Foundation for Science and Arts.

Bibliography

Bârsan, Cristina, Dimitrie Cantemir and the Islam, Bucharest, The Publishing House of the Romanian Academy, 2005; Hammer-Purgstall, Joseph von, Geschichte des osmanischen Reiches, Budapesta [Pest], C. A. Hartleben, 1827-1835,10 vol; Kantemir, Antioh Dmitrievič, Satyres du prince Cantemir, traduites du russe en françois. [Par de Guasco, Londres, J. Nourse, 1750.

.jpg)