The building inscription of a temple belonging to a Palmyrene community from Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

Text: dr. Ovidiu Țentea

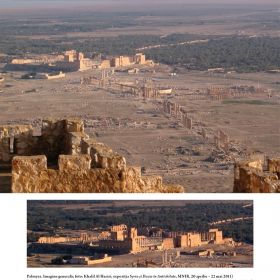

Palmyra (initially named Tadmor) was an ancient settlement mainly defended by natural barriers: desert and mountains to the North, West and South-West (the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon Mountains which block the connection with the Mediterranean seacoast), while to the East and the South the Hauran Desert. The first inhabitants of the city were the nomadic Amorites, attested since the 18th c. BC. They used the Aramaic language, related to the Hebrew language and using the same alphabet, an idiom which will become a lingua franca during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (10th - 7th c. BC). The religion and customs were those of the local Ammonite population, having an Arabic component, later constituted by the wave of Nabataeans from the South and other diverse ethnic groups. There was also a component of Greek civilisation, namely Hellenistic, dating since the time when the area was part of the Seleucid Kingdom. The characteristic of the civilisation of Palmyra was the melange of Arabic, Aramaic, Greek and Roman elements.

The native Arabic settlement was transformed in time from a stopping place for caravans into a first rank city of the antiquity. The ancient historian Appian mentioned that in 41 BC Mark Antony undertook a campaign in Palmyra, known for its commercial relations with the Parthians, since he hoped “to obtain a profit for his knights”, but the Palmyreans (in their majority nomads settled in an oasis) left the city by “melting into the desert” and thus the Romans returned with empty hands. Out of the anecdotic account of Appian results the independent nature of the trade practiced by Palmyra at the middle 1st c. BC. The privileged status of Palmyra within the province of Syria was perpetuated, as it is outlined by the account of Pliny the Elder in 77 BC. This particular status does not explain the extraordinary ascent of Palmyra during the 1st c. AD, but a possible reason might be the interest to move the access to the harbours at the Mediterranean Sea, from Antiochia to the Phoenician ones from Tyr and Sidon, better furnished for the textiles’ shipping. The main hindrances of a direct commercial route towards the Mediterranean Sea were the desert and the nomad character of the population in Palmyra. While the trade activities grew in intensity in this area, the oasis’ population started to settle, and on the same time grew the degree of safety for the caravan transports.

The flourishing period of the city of Palmyra coincides with the one of the Roman domination in Syria, when the city becomes important due to the decision to cross the desert through trade routes against the bypassing variants. It seems that the settlement turns into a tributary to Rome, having a garrison since 19 AD, when is attested the name of Palmyra, which replaces the previous one of Tadmor. Trajan’s campaign against the Parthians, at the beginning of the 2nd c. AD, determines major problems for the metropolis, since its prosperity was closely linked to the keeping of good relations with both powers, given the fact that the caravans’ routes on which the city pertain were situated on a zone of “no-man’s land” type. Palmyra benefited on its location in order to provide to Rome the luxury products of the Far East (silk and spices), while the Parthian Empire was interested in the western products. The luxury goods like the silk, the jewels, the pearls, the fragrances and the spices were brought from India, China, South Arabia and took out annually from Rome’s treasury the amount of 100 million sestertii, according to Pliny the Elder. There was a tacit agreement between the two parts which allowed Palmyra to become an intermediary in trade which generated enormous profits. Appian accounts that the Palmyreans “being merchants, brought goods from India and Arabia through Persia and they distributed it in the Roman territories”. The chiefs of the caravans, genuine “merchant-princes” are mentioned in numerous inscriptions, since they were organised in authentic trade companies.

The climax period of the metropolis was during the years 130–270 AD, when are dated the majority of the epigraphic and sculptural monuments. Now Palmyra has the trade’s monopoly with the regions situated beyond the eastern border of the Roman Empire and also held the right to set the price at the stock exchange.

Emperor Hadrian treated the city with special favours and, on the occasion of his visit here in 130 AD, raised it to the rank of municipium, named Hadriana Palmyra, undoubtedly as an attempt to encourage the resume the trade with the Parthian Empire following the conflictual situation during Trajan’s reign. At the same time, the custom taxes were reconsidered (137 AD) by replacing the older tax system with the model of the Greek municipalities of the empire. Sometime during the reign of Septimius Severus or Caracalla (on the first half of the 3rd c. AD), Palmyra receives ius italicum and the rank of colonia. During this period are attested more Palmyreans who become citizens, bearing the nomina imperialia Septimius or Iulius Aurelius, together with their traditional names as cognomina.

The city’s control extended over a vast neighbouring area, including villages or territories inhabited by nomadic populations. The villages and the tribes provided to the Palmyrean militia excellent dromedary archers, since the recruitment from the actual metropolis area being difficult to achieve.

The degradation of the balance between the Roman Empire and its eastern neighbours, Parthians or Sasanians, threatened the well being of the Palmyra in many cases, like during the campaigns of Crassus (54 BC), Trajan (114-117 AD), Caracalla (216 AD), in order to culminate with the collapse of the city which occurred as a result of a prolonged political crisis. The emergence of the Sasanids created new difficulties for the empire, having as background internal dynastic crises: the banishment of the Roman citizens out of Mesopotamia, commencing with Ardashir around year 230 AD, while later his successor Shapur I defeated a Roman army in 244 AD. Dura Europos fell in 256 AD, and Palmyra was next to be conquered. Shapur’s triumph was crowned by the capture of Valerian in 260 AD. In such a context entered the stage Odenathus and his wife, Zenobia. The military victories in Rome’s favour, against the Persians in 262 and 267 AD, then the invasion of Egypt, in order to gain control over the trade routes in here due to the blockage of the traditional commercial routes eastwards of the Euphrates, led to the fracture of the liaisons with Rome. Aurelian gain back both Egypt and Palmyra in 272 AD, the city being largely destroyed. The metropolis will never recover, its elite taking refuge into the desert zone, thus becoming again an aristocracy of sheikhs of nomadic populations.

The liaisons between the provinces of Dacia and Syria have more explanations beside the integration within the same Empire. Emperor Hadrian was governor of the province of Syria during the Parthian war fought to the end of Trajan’s reign. The close relations between emperor Hadrian and Palmyra explain why during the war at the borders of Dacia, in 117-118 AD, he send in here an elite units originating precisely from Palmyra. This group was composed of mounted archers, extremely skilful and efficient against nomad populations. This contingent was named Palmyreni sagittarii (Palmyrean archers) and will be divided in three units (numeri). For two of these numeri are known the garrisons, namely at Tibiscum (Jupa, near Caransebeş, Caraș-Severin county) and Porolissum (Moigrad, near Zalău, Sălaj county), while the third allegedly stationed somewhere near Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.

Among these soldiers and veterans were formed in Dacia communities of Palmyreans, who later became Roman citizens. They were followed by rich merchants from Palmyra, who had relations with the caravans which travelled in Orient. Many of them were part of the municipal elite from Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and other cities of Dacia, being possible to be recognised by their specific names: Theimes, Zabdibol, Audeo, Malcus, Iacubus etc. The most important Palmyrean communites attested by epigraphic sources are known at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.

Sarmizegetusa, by its complete name Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa, is not a common Roman settlement. It was the first city and remained the most venerable city of the province of Dacia. Emperor Trajan wanted to make of it a symbol of the Roman power and splendour. Trajan’s forum (forum vetus), the new forum (forum novum) with the capitol, the amphitheatre, the temples of area sacra are superb and representative edifices for the Roman architecture. Sarmizegetusa was named by tradition the capital of the province of Dacia, although the governor’s seat was at Apulum (Alba Iulia). At Sarmizegetusa was located the seat of the financial procurator of Dacia Apulensis, in here being the gathering place for the concilium trium Daciarum, which had as main attribution the celebration of the imperial cult on behalf of all the communities in the province. The imperial cult was in close connection with the one of Jupiter and of the Capitoline Triad, at Sarmizegetusa being built the first capitol of the province. According to the estimates, Sarmizegetusa had about 20,000-30,000 inhabitants, a number which placed it among the cities of medium size in the Empire. The city was led by magistrates (duumviri iure dicundo) and a municipal senate (ordo decurionum).

The first temple of the Palmyrean gods discovered at Sarmizegetusa

The temple was located extra muros, westwards from the fortified precinct of the city, on the ridge of the Delineștilor Hill, on the confluence of the Drașcovului and Bocului valleys. The building, oriented East – West, seems to be the only construction which has existed on that hill on those times, its ruins being untraceable at the surface during the last decades.

The temple was investigated in 1881 by the archaeologists Téglás Gábor și Király Pál. The excavation technique employed at that time by Király Pál might be an explanation for certain omissions which many archaeologists tried to correct later (Dorin Alicu, Alfred Schäfer, Alexandru Diaconescu). The data are provided in a report drafted by Téglás Gábor 25 years after the completion of the excavations.

According to Téglás Gábor, a fragmentary altar was discovered in here in 1873, and it’s highly possible that this inscription is similar to the one published in corpora – IDR III/2, 345 = CIL IIII 7963, both indicating that is was uncovered in 1878 on the “Drașcovu” spot.

The religious manifestations of the Palmyrean soldiers, and in general of the diaspora of Palmyra are dedicated to the “national” gods, common for the Palmyreans, the so-called dis patriis, by renouncing to the tribal or familial aspects. The gods adored prevalently by this population on the territory of the Roman Empire were Bêl (the supreme divinity), Iarhibôl, Aglibôl or Malakbel. The situation is different in the case of the foundation inscription of the first temple of the Palmyrean gods, discovered on the western part of Sarmizegetusa at the end of the 19th c. Some other inscriptions dedicated to the Palmyrean gods were found at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, outside the precinct walls, but they were not set in connection with the buildings where they once were located.

The temple was dedicated to the fatherly gods (Diis patriis), but the pantheon of Palmyrean divinities is a surprising one, being mentioned: Malagbel, Bêl Bêl Hamon, Benefal (Fenebal) and Manavat. Another striking aspect is the fact that Malagbel (messenger of Bel – the supreme god) was placed at the beginning of the adored gods, an explanation being the influence of the soldiers who venerated him as a Sun god in the entire Empire.

Some authors consider that Malagbel was mentioned before two divine couples: a Phoenician one Baal – Hamon – Benefal (Tanit), while the other one comprised Bel Belhamon – Manawat. This last couple was identified as the divine pair adored in a temple on the Jebel Muntar hill, which dominated the western zone of Palmyra.

The local origin for Bel – Hamon was seen as a local combination of the civic tribes from Palmyra, namely Bene Agrud, to which might have pertained Publius Aelius Theimes. This built the temple as a gathering place for the small Palmyrean community Bene Agrud in Sarmizegetusa.

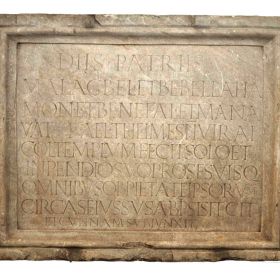

The foundation inscription of the temple, kept in the MNIR collections (inv. no. 38939) is made of marble, extracted from the quarry at Bucova (about 11km westwards from Sarmizegetusa). Size: 131 × 88 × 18 cm (IDR III/2, 18 = CIL III 7954).

The epigraphic field is outlined by a simple frame. On both parts there is a triangular gable with two acroteria. The decoration is made of leafs and vegetal motifs in shape of succesive strygilles.

Dis Patriis

Malagbel et Bebellaha

mon et Benefal et Mana

vat P(ublius) Ael(ius) Theimes II viral(is)

col(oniae) templum fecit solo et

impendio suo pro se suisq(ue)

omnibus, ob pietate(m) ipsorum

circa se, iussus ab ipsis, fecit

et culinam subiunxit

Translation:

To the Parental Gods

Malagbel and Bel Bel Ha

mon and Benefal and Mana

vat Publius Aelius Theimes duumviralis

of colonia (Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa) made a temple for himself and all of his own

by the benevolence of the Parental Gods to himself,

at their order made it

and added to it a culina.

The text informs us that the temple of the “parental gods” was erected entirely on the expense of Publius Aelius Theimes, a former magistrate (duumviralis) of Colonia Sarmizegetusa. His generosity was a response to the divine grace (Pietas Deorum) and to the direct request of the same gods (iussu). It is also mentioned that he added as well as kitchen (culina).

The inscription attests a temple of a Palmyrean tribe of Cannanite-Arabic origin. In the centre of the tribal cult was the divine pair Bêl Hamon (at Sarmizegetusa – Bêl Bêl Hamon) and Manawat. The pair of Bêl Bêl Hamon receives a divine epithet used only by the western Phoenicians. As a result, the ancestors of Publius Aelius Theimes would have come at Palmyra from the Phoenician coast. Despite that this character was on top of a hierarchy of the Roman metropolis Sarmizegetusa, both an iconic and cosmopolite city, he insists to specify with great attention both his origin of the civi tribe from Palmyra, as well as his Phoenician ancestry.

A second inscription discovered in this temple is kept in the collections of the Museum of Dacian and Roman Civilisation in Deva. It is made of a local marble slab (from Bucova), which might have been situated in the central aisle of the temple (IDR III/2, 262 = CIL III 7955).

Deo San[cto] Malagbel[o]

pro salut[e Imp(eratoris) C]aes(aris) M(arci) Aur(eli)

Severi [[Alexandri]] Pii fel(icis) aug(usti)

et Iuliae [[Mameae]] augustae

matri aug(usti) n(ostri) et castrorum

Primitivos aug(usti) lib(ertus) tabularius

prov(inciae) Dac(iae) Apulens(is) posuit.

Translation:

To the saint god Malagbel

for the health of Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Severus Alexander

the happy pios Augustus and to Iulia Mamaea Augusta

mother of our emperor and of the forts

dedicated by Primitivos, imperial freedman,

tabularius of Dacia Apulensis province.

The second cult edifice where have been found inscriptions dedicated to the Palmyrean gods was recently identified in the central part of the city. The archaeological excavations undertaken between 2007-2011 led to the discovery of a cult place / seat of a college which bordered to the West the forum of Trajan and to the North the forum of Antoninus Pius. The edifice consisted of a stand (podium, a very solid platform) made of river stones bound with mortar and powder of bricks. This stand is a rectangle with a side of 8.50m, having a difference of level to the front courtyard of about 2m. The entrance was on the eastern side, by a series of marble steps, and in their front was the altar. The temple was built on the podium and had on the front side four Corinthic columns (tertastyl). There have been found impressive quantities of marble – stairs, slabs for the walls, fragments of column trunks and Corinthic capitals, votive reliefs– and numerous fragments of inscriptions.

An inscription, made on a marble slab, attests a triad of divinities from Palmyra, in front of which is Bel (Sol Invictus), out of which can be than distinguished Malagbel and Ierhabol. The aspect of the inscription is very similar to the second inscription of the first temple of the Palmyrean gods discovered at Sarmizegetusa. The date of the inscription is the same as for the above mentioned one, being place for the health of emperor Alexander Severus (222–235) .

Another inscription attests a college of worshippers of god Malagbel.

A third inscription preserves partially the name of a Palmyrean divinity, Iarhibol.

The archaeological excavation of the new Palmyrean cult edifice at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa is ongoing.

This presentation is a hommage to all the ones who studied and defended with their lifes the heritage of the ancient city of Palmyra.

Această prezentare este un omagiu adus tuturor celor care au studiat și apărat cu prețul vieții patrimoniul orașului antic Palmyra.